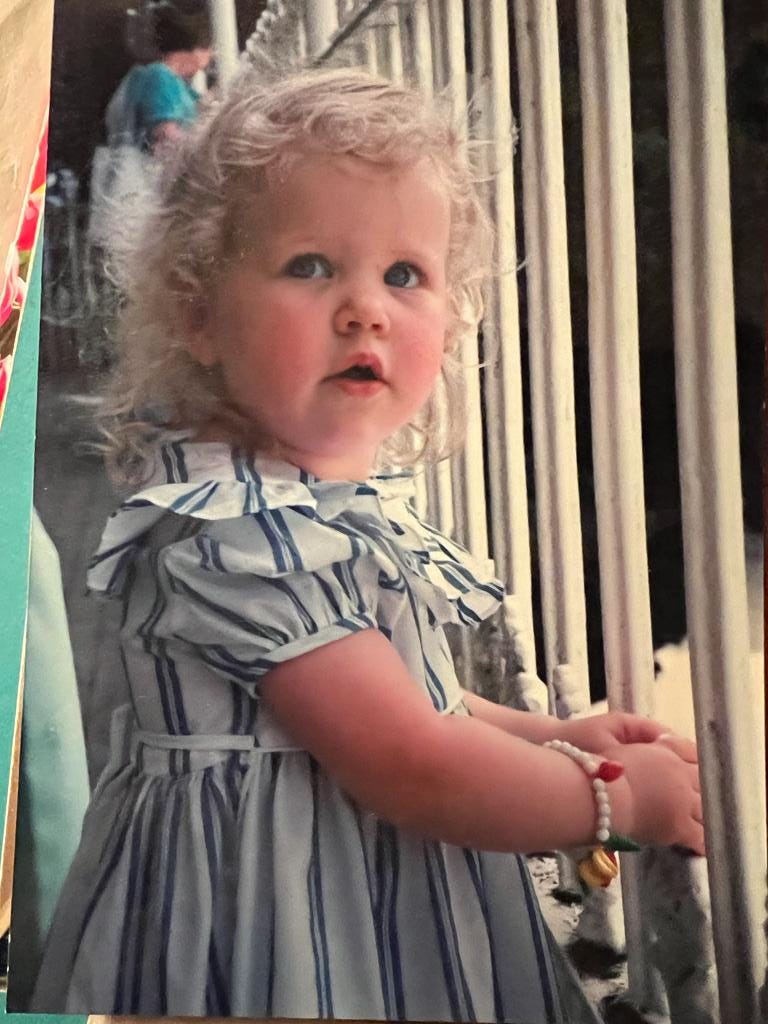

1989

It must have been winter, because on cold mornings Dad wore a warm woolen cardigan, coloured red and edged with black. The cardigan unlocks this memory: Dad’s red and black cardigan, its forward pocket jutting out like a brazen lower lip; his thick glasses, mock-tortoiseshell and hornrimmed; the newspaper unfolded before him on the living room table, the freshly-shaven face silently studying it; and the dark hair unruly, by his standards, though trimmed short.

His long legs are crossed, the trousers dark. Having attended to his customary bowl of porridge already, and the tea still brewing in a pot on a brown wooden stand that exists to this day on the kitchen mantle. The tea brewing, and now an inscrutable signal animates the hitherto still image: Dad pours the tea out from the pot, and vapours of steam pour aloft from the full cup.

Details of the room’s composition begin to filter in — the brown circular breakfast table, papered opulently with the broadsheet, stands beside the pass-through from the kitchen, and his chair faces me in the doorway. I must be seated at the children’s table to observe him from this vantage. I am seated in a small chair, attending to my own mushy breakfast, and the light is dim because it is a dark, foggy morning outside and there are only two windows on the easterly side of the room (but I cannot remember their shape — square? oblong?).

This is an ordinary morning, very familiar and silent. The red cardigan serves as the heraldic symbol of the ordinary and familiar; the everyday objects that parade around the cardigan — teapot, porridge, glasses — bring steadiness and comfort to an otherwise volatile stream of recollections. This morning Dad must have woken me up and carried me from my navy-edged bassinette with its white netted railing this morning, because there is no sign of Mum yet. Where is Mum?

Now the perspective shifts, the head turns with it: the kitchen is behind me, Mum has appeared, and she is pacing across the black and white square tiles with Patrick in her arms. She has appeared! Mummy! The kitchen is significantly lighter and brighter than the living room; Mum is wearing a dressing gown of pale soft chenille (blue?) with two large pockets in the front of it. Her hair is mid-length and tousled; the features of her face inexpressive but the eyes gleamingly motherful. It looks as though she has only lately got up from a night of not-very-much sleep. She is beautiful in the poignant way that only mothers can be beautiful, and Dad is so impressive, steady and sure of his every action and movement.

I think, at this point, that there is a terse exchange of questions and answers between Mum and Dad, but what is said does not register. And now the preparations begin for Patrick’s bottle; the silent vigil over breakfast has transformed, with Mum’s appearance, into a series of directed actions, noisy and busy, in which I play no part.

I do not yet understand the concept of readiness but at some moment that follows soon after we are deemed ready to have our kisses goodbye and head out the back door to go to my daycare across the lane. There it smells strongly of disinfectant and we are attended by carers of vast amplitude beneath the blazing fluorescent globes of the playroom, and the linoleum squeaks beneath our stumbling sneakered footfalls as we race towards the collection of shabby, used toys.

1992

I am interested in the freckled boy named Tristan, or maybe it is Christopher. Many of the names I ascribe to the other children at school are based on how they appear to me, not what they are called; often, I am surprised when a girl I had assumed to be Sarah turns out to be Kate, but then I often fancy that she is just pretending to be Kate but is secretly Sarah. Primary school is a complex embroidery of mostly imaginary stories. Being a shy child, and not having yet found a particular friend of my own, I mostly keep to myself and amuse myself by thinking that I know everybody’s secrets.

But there is a heavier influence that portends my solitary schooldays, and that is the gruesome feeling that seeps into my chest from the moment I alight the safety of a familiar vehicle each morning and step into the school grounds. At home I am chatty and lively and inclined to theatrics; at school I am subdued and spend the day avoiding people. Nobody is ever allowed to see me eating; the times of the day assigned for eating make me nervous beyond anything, except perhaps when I am called to the blackboard to solve a problem before the class.

Each day I privately unwrap my little bundle containing a sandwich, fruit, and a pair of vegemite-smeared Salada biscuits — usually hiding behind the girls toilets where there is a brick wall overlooking the neighbouring schoolyard. All of the lunchbox items (with the exception of a chocolate-chip muesli bar, which I always eat) fill me with a sense of unspeakable dread. The mere thought of unwrapping the sandwich or biscuits from their clingfilm disgusts me, not because I dislike these foods (at home, I am a happy eater) but because here they are simply not allowed. The odour of home hangs heavily upon everything, and the feelings it evokes do not belong at school.

It is one of my everyday rituals to discreetly dispose the contents of my lunchbag (with the exception of the muesli bar or some other supermarket-bought snack) into the garbage bin beside the playground. The hot canteen food usually poses no problem, if consumed unobtrusively. Lying about what happens to my lunch each day is not, of course, an ideal scenario but it is easier to lie than to try and explain the intricate webs of foreboding that overhang my life in Grade One, the private rules of what is allowed and not allowed at school.

I wonder where Tristan is playing? Or is it Christopher… Even though I would never approach him (I only ever approach Valerie and Briar, because they are Usually Nice though Sometimes Bossy) at breaktime I am always interested to know where the freckled boy is and what he is doing and if he understands.

1999

We do not know it yet, but my parents will be telling us about their divorce only three months from now. Patrick and I are on holiday with our grandparents during the winter holidays, and everybody seems happy so we must all still be in the dark. The weather is subtropical and humid here on this island; our grandparents take us to places like this so that we can listlessly follow them around for their interminable rounds of the golf course.

I am only twelve and I have not yet learned how to dress or to talk to people socially. There is a meetup group for teenagers younger than fifteen at the resort, which my grandparents encourage me to take part in (probably knowing how uncomfortable it will make me). It turns out that the other people there are friendly and nice, yet all of them seem more relaxed in themselves and at ease with self-presentation than I.

It is not only the braces on my teeth and the unmanageable yet too-short nest of curls that I must reckon with, but the startling absence of anything smart or funny from my conversation. Having only recently graduated from Garfield comics, my taste is still unformed and unworldly. I desperately wish to say smart, funny things that will make everyone laugh; inevitably, all my contributions sound brash and annoying.

The other teenagers — the normal, well-adjusted ones who have Figured Things Out — fascinate me endlessly. Soon we become a little clique and spend idle afternoons together at the poolside, and I feel totally out of my league, almost like I should be taking notes from these people on what to say and how to act. Do they like me? They seem to accept me, even to appreciate my company; but everybody knows there is a given limit to holiday friendships, and even I cannot fool myself into thinking that my link to these Cool Friends will outlast this place and time.

I can tell you about the moment when Shit Got Real. I come back from a round of golf with my grandparents and set out on a circuit of the resort with my headphones in (because it looks cool!) looking for my friends in the normal places we would meet; the games room, the swimming pools, outdoor lounge. Imagine my astonishment, imagine my shock and disbelief, when I round the path that leads to the hot tubs only to see Hayley and Richard kissing. Making out! Pashing on! And I thought they were my friends. I had thought that all of us were friends.

Retreating from the pair with a horrific surge of adrenalin in my breast, the truth of the situation at last dawns upon me. I had been so green, so naïve in the real intricacies of our group. The only reason that everybody was so nice and friendly — nice even to unfunny, awkward, annoying me — was because that was the socially acceptable way for young people to desire each other. Hayley and Richard had probably been out for this all along and were just waiting for the rest of us to clear off to make a move.

Following the curvilinear pathways away from the kissing couple, I feel somewhat dejected and unhomely. My anticipation to see these friends again has transformed into a sensation that verges on heartbreak, but is really just the thrilling disappointment of expectations unmet.

We do not know it yet, but my parents will be telling us about their divorce only three months from now. The disquiet I feel in this moment prefigures this awful revelation, and really frames the whole experience of adolescence. Imagining myself as a victim of a plot or hidden agenda, all of my efforts towards acceptance are driven by the fear of being once again left out.

2003

A boy in a shabby suit with black hair is lying on his back on the lawn behind the party, watching the stars. I am curious about why he is there on his own. Thinking that something might be wrong, I approach him to talk — kneeling first on his right side, then sitting cross-legged, and finally stretching out on the grass myself as we swirl into a depth of conversation such as I have never before entered into with a stranger.

We are talking about life as the food of art, the substance with makes art vital and immediate. There is no point in living, we agree, unless there is something to be made of it; and he is saying that the best art is powered by raw and intense experience. The black-haired boy is clearly drunk, yet I am exhilarated by the tone of this conversation; it seems to touch so much deeper than the usual party banter, it seems to speak so naturally to the yearnings of my soul.

But the main consequence of this fleeting moment of connection on the grass in Demian’s backyard was not that either one of us ever managed to make great art from our intensity, but that we succeeded — over the three-and-a-half years that followed — in making each other deeply miserable.

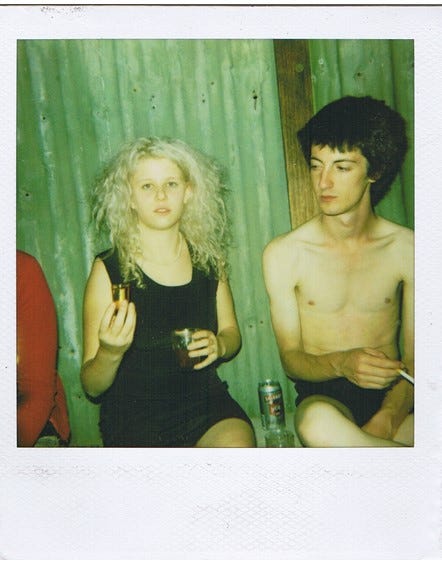

2006

Everyone is out and about on the streets of Edinburgh, for it is the first weekend that properly feels like summer. On the way home from my café job on Rose Street, I cross into Princes Street Gardens to discover the lawn filled with merry picnickers; university students idling after their exams, paunchy office workers gathered in clusters with bottles of lager, a few hippies and ravers wandering barefoot on the grass.

The great Castle looms overhead, casting its sepulchral shadow across the park; I am passing through it on the way to Cockburn Street where I am living in a youth hostel in exchange for cleaning work. Between these two menial jobs, existence is bleak and pleasureless. I am saving money to buy a ticket back home. My only friend in this city is Krzysztof, a conspiracy theorist and UFO enthusiast nearly twice my age; he might be waiting for me back at the hostel to share a cigarette and a few paranormal anecdotes, unless he is grumpy. Krzysztof hides from everyone when he is grumpy.

Amidst the swarms of happy people filling up the park, I am so miserable that it feels like I am a different species of human. Wearing hospitality blacks and heavy combat boots in which my tired ankles are spasming, the spine is curled in a posture of despair and my neck aches terribly. Whatever thoughts pass through my mind are complaints or convictions of injustice; and occasionally memories of happier times flit through, which evoke my longing to go home where people love me, even as I dread the repugnant truth that, at nineteen, I do not know how to make it in the world alone.

2007

It is a crisp autumn afternoon and I am drinking goon with Chalmers on the roof of her house. It is the old Dial-A-Roof storefront on Lygon Street, East Brunswick, in which she has been squatting for the last month with an anarchist and a graffiti artist. She calls the place Stone Soup; I have named the alleyway behind it Zombie Dance Lane.

We are drinking our stale plonk from crystal-glass tumblers that Chalmers found at the op shop; she has the uncanny ability to unearth all kinds of treasures, and has strewn her bedroom here with feathery boas and old costumes and vintage tea-sets and animal bones and pewter goblets.

Suddenly Chalmers turns to look at me, her eyes electric: “I know where Daddy keeps his speed!” (‘Daddy’ was our name for her anarchist housemate; we were a bit bitchy like that sometimes).

Leaving our tumblers on the roof, we climb down into the sparsely-furnished loft in which Daddy has installed a suspended bed. Casting the theatrical look of a mischievous child at me, Chalmers rummages through the secret hiding place and presently fishes out a miniscule plastic baggie half-filled with a lumpy substance the colour of sand.

I have taken lots of party drugs before but never raw speed. I am not expecting it to be brown, but there is no sense in acting fussy. Chalmers has already set up a level surface on the bed and is busy preparing lines.

“Teensy weensy ones,” she says. “He probably won’t even notice.”

They are very small lines. We inhale them quickly, then rub a bit more dust on the surface of our gums, and then a little bit more again. Chalmers restores the baggie to its secret hiding place, removing all the traces of our trespass, and we move to ascend to the rooftop again. It is nearly sunset.

The speedy feeling hits me as we climb the roof. It cuts through the confusion of my mind like a sharp, well-positioned knife: this is what I need to be doing, this is perfectly right. I do not experience a thrilling high, but rather a cold, clear knowing of my motivation and purpose. I have thirsted all my life for this feeling of clarity — everything, it seems, at last makes sense.

A threshold has been crossed (though I do not know it at the time) that will wend me along a peculiar and specific pathway of pursuing amphetamines in every available form, with whatever meagre funds I could earn to sustain my nascent habit: the sandy lumps of dust, the searing powders of white, the vapours of stinging ice, and finally (once my habit had graduated into an unassailable personal conviction) a prescription to extravagant quantities of the the pharmaceutical-grade stuff.

(But then Chalmers — bless her loving heart! — was the first one to scold me about my drift, a few months later, towards the companionship of “too many bad people and their nasty drugs.” If only I had listened.)

2009

I leave the party early, verging on an anxiety attack; it is a short walk home from Fitzroy, and I turn in the direction of Victoria Parade, white cowboy boots clomping on the asphalt as I dip between shadows cast by the chain of amber streetlights. I have on my houndstooth jacket with seamed-up pockets that only my thumbs can slip into, but the season is turning cold and I am shivering through it. I keep a brisk pace to stave off the chill and to reassure myself that I am safely escaping.

Sometimes it happens, though it is a rare occurrence, that the sense of dread and overwhelm that I bear within me accumulates to such an extent that it becomes impossible to connect with people in an ordinary way. It had been a crowded party, very noisy, and after half an hour of standing around and trying to fit in my vision began to swim and the air contracted in my chest. The only antidote to this state of nervous tension is to go home and have a hot bath; and so I had set off into the night with just my thoughts for company, trying to make sense of what is going on inside.

Why is it that I always end up alone? I move to cross Victoria Parade near St. Vincent’s hospital, pausing to let a few cars go past before approaching the tramway fringed by narrow lawns. Traversing the nature strip: what does it all mean that I feel this, that I am this? Is there something better that I could be doing? Who am I becoming? The lane leading towards the city is void of traffic; I cross, turn left, continue in the direction towards East Melbourne.

Just before making the right turn into Simpson Street, which leads past the tennis courts and directly home, I confront a cold longing to go further in my art than anyone could reach me, deep enough to lose myself, to disintegrate in the thrill of dreaming. I want to forget who I am and create something from the void, something better than what I am, something new. And with the powerful sense that I have resolved this crisis into something purposeful, I turn into my neighbourhood and begin to stride towards home.

You can download the ebooks for the first three volumes of Surrender Now using these links.

-